Summary

When it comes to skyscrapers, rigidity is the enemy. Engineers actually design tall buildings to sway during high winds — a counterintuitive but necessary approach to keep them standing. In this blog, I’ll explain why stiffness can be dangerous, the pros and cons of flexible design, and the clever methods engineers use to make residents more comfortable. I’ll also share the story of the infamous John Hancock Tower in Boston and how engineers resolved its sway problem, along with lessons from Taipei 101.

Why Engineers Design for Movement

If you’ve ever stood at the top of a tall building during a storm and felt it sway, you might have wondered: “Shouldn’t this thing be rock solid?” The answer: no, and thank goodness it isn’t.

Rigid buildings don’t dissipate energy well. When hurricane-force winds or seismic loads hit, a stiff building risks cracking or even catastrophic failure. Flexibility allows the structure to absorb and release energy safely (American Society of Civil Engineers, ASCE 7-22).

Think of it like palm trees during a storm. A stiff oak might snap, but palms bend and survive. Skyscrapers are the palms of the built environment.

The Pros and Cons of Building Flexibility

Pros

- Safety: Prevents catastrophic structural failures.

- Durability: Flexibility reduces long-term cracking and material fatigue.

- Code Compliance: Modern building codes (including Florida Building Code) require sway allowances.

Cons

- Motion Sickness: Occupants can feel the sway, especially on upper floors.

- Psychological Discomfort: People expect buildings not to move — even when it’s normal.

- Design Complexity: Engineering sway solutions requires specialized modeling and costly construction features.

In South Florida, where high winds are part of life, engineers carefully balance these tradeoffs.

Techniques to Reduce the Feel of Sway

Engineers can’t eliminate sway, but they can reduce the feeling of it. Some tactics include:

- Tuned Mass Dampers: Giant counterweights that move opposite the sway to steady the building (like in Taipei 101).

- Outrigger Systems: Structural beams that tie the building’s core to exterior columns for added stiffness.

- Aerodynamic Shaping: Rounded corners or notched designs that reduce wind pressure.

- Window Design: Covering or shading windows so occupants don’t visually track the building’s movement.

These approaches don’t make the building perfectly rigid — they just make the ride smoother for those inside.

Famous Case Study: The John Hancock Tower

Let’s step away from Florida for a moment and talk about Boston’s John Hancock Tower.

When it opened in the 1970s, it quickly became famous for the wrong reason. The 60-story tower swayed so much in the wind that people on the upper floors felt seasick. Some even reported furniture sliding across rooms. To make matters worse, massive glass windows began popping out and crashing to the streets below.

The solution was complex: engineers added tuned mass dampers — giant weights that counteracted the sway — and retrofitted the glass. Over time, the fixes worked, but not before the building became a cautionary tale for structural engineers worldwide.

Another Marvel: Taipei 101

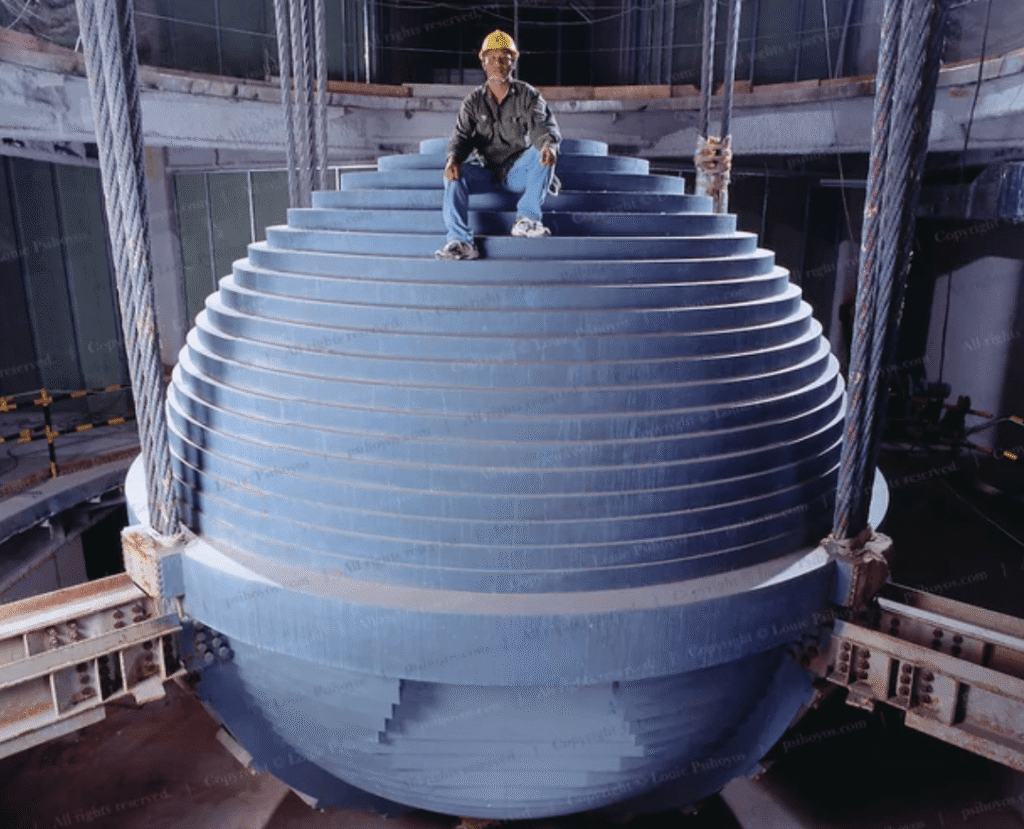

On the other side of the world, Taipei 101 tackled sway head-on. The 1,667-foot skyscraper includes a 660-ton tuned mass damper — a golden sphere suspended between floors near the top. When the building sways in typhoon winds or earthquakes, the damper swings in the opposite direction, balancing the movement.

The damper isn’t hidden away, either. Visitors can actually see it, which reassures them that the sway is not only expected but also controlled.

True Story to Learn From

Now, let me bring it back home to South Florida.

I once had a client in Miami who bought a penthouse condo in a new high-rise. After the first tropical storm of the season, she called me in a panic. “Greg, my chandelier was swaying last night! Is my building safe?”

I explained that yes, the building was safe — it was designed to sway. But explaining “safe sway” to a nervous resident takes some finesse.

We walked through the building’s design: its wind bracing, dampers, and compliance with the Florida Building Code. Then I told her about Taipei 101’s damper, adding: “If they can make a skyscraper in Taiwan dance with a 660-ton pendulum, your condo can handle a tropical storm.”

She laughed, and I could see the relief on her face. The next time her chandelier swayed, she texted me: “Greg, I think my condo is dancing.” Mission accomplished.

Different Perspectives

Some argue that skyscrapers should be built to eliminate sway altogether. While that sounds comforting, it’s structurally dangerous. A perfectly rigid building would snap under hurricane winds — a fact supported by wind engineering studies (National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST, 2012).

Others believe occupants should simply “get used to it.” But ignoring comfort creates unhappy residents, complaints, and even legal disputes. That’s why engineers design not only for safety, but also for human psychology.

The balance is key: buildings must sway, but people must feel safe while inside them.

| Factor | Typical Measurements / Statistics | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Wind Pressure on Tall Buildings | ~1–2 kPa (kilopascals) on building facades during strong winds; hurricane winds can exceed 3–4 kPa | Wind pressure increases with wind speed and height. |

| Sway at Top of Tall Buildings | High-rises are designed to sway 0.1%–0.25% of their height. • 200 m building → 20–50 cm sway • 400 m skyscraper → 40–100 cm sway | Engineers allow controlled movement to prevent structural damage. |

| Human Comfort Threshold | Sway causing accelerations above 15–20 milli-g (0.015–0.02 g) becomes uncomfortable for many occupants | Cross-wind motion is typically more noticeable than along-wind. |

| Natural Frequency of Skyscrapers | Usually 0.1–0.5 Hz (one oscillation every 2–10 seconds) | Tall buildings are intentionally flexible and have long vibration periods. |

| Vortex Shedding Frequency | For rectangular tall buildings: often 0.1–1 Hz, depending on wind speed and building width | If this matches a building’s natural frequency, it can amplify sway. |

| Tuned Mass Damper Effectiveness | Can reduce lateral motion by 30–50% in strong winds | Large weights (hundreds to thousands of tons) counteract sway. |

| Soil Flexibility Contribution | Soft soil can increase lateral drift by 10–30% compared to bedrock foundations | Foundations interact with the ground during wind motion. |