Everyone wants a quick fix for broken concrete, but there’s no magic dust that can reverse years of rust, spalling, and neglect. In this blog, I’ll explain what spalling is, why chemical shortcuts don’t work as long-term solutions, the truth behind “miracle” products, and what real engineering repair methods like cathodic protection and ICRI-standard patching actually involve. I’ll also share a true story from Hollywood, Florida, where a board almost made a very expensive mistake.

The Myth of the Magic Dust

I get this question more than you’d think: “Can’t we just sprinkle something on the concrete to stop the rust?”

It sounds like a great idea. Just toss some miracle powder into the cracks, maybe wave a wand, and—poof!—the steel inside stops corroding, the spalling disappears, and everyone saves millions. Unfortunately, buildings don’t work like fairy tales.

The standard, time-tested way to fix spalled concrete is:

- Chip out the damaged concrete.

- Expose and clean the corroded reinforcing steel.

- Apply protective treatment to the steel.

- Patch with high-strength repair mortar or concrete.

This is not just tradition—it’s science. The steel inside concrete (rebar) rusts when chlorides and moisture get in. Rust expands up to 7x the volume of the original steel (Source: American Concrete Institute ACI 562-19). That expansion causes cracking and more spalling. It’s like dental cavities—if you don’t drill out the rot, it keeps spreading.

Still, over the years, manufacturers and sales reps have pitched “shortcut” solutions. Let’s look at a few of them.

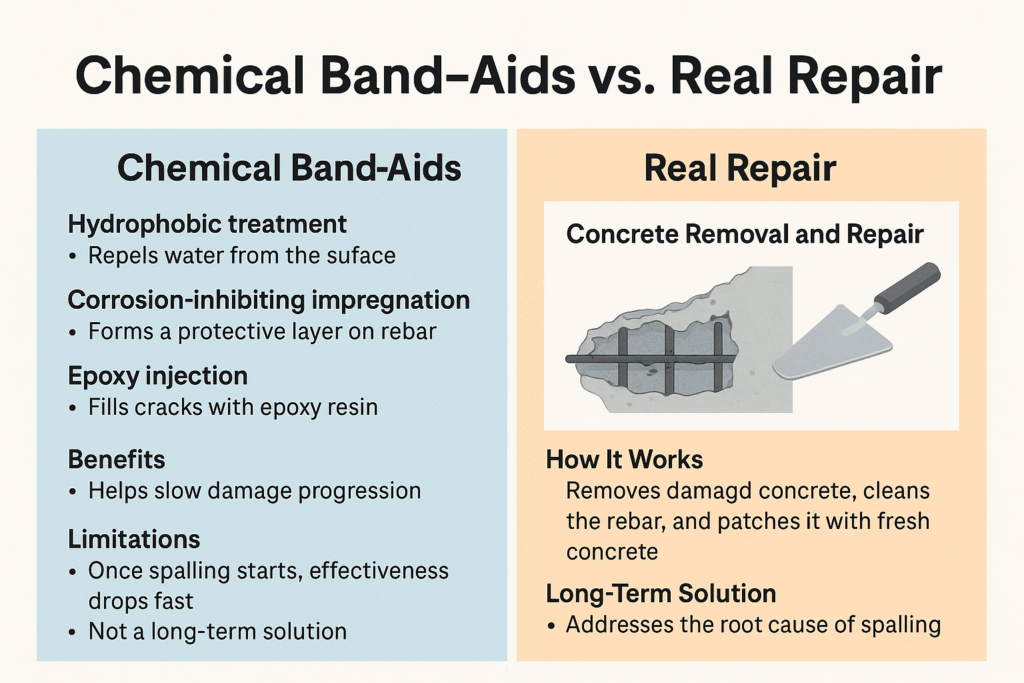

Chemical Approaches People Ask About

1. Hydrophobic Treatments

How they work: These are surface-applied chemicals that repel water (think Rain-X for your building). The idea is to keep moisture from soaking into the concrete.

Benefits:

- Easy to apply—usually a spray or roller.

- Can reduce water absorption.

- Useful for protecting sound concrete before corrosion starts.

Limitations:

- They don’t stop chloride ions (from salt air or seawater) from migrating through cracks.

- They don’t repair already damaged areas.

- Like sunscreen, they wear off and need reapplication every few years.

When to use: Great as a preventative measure, especially in South Florida coastal areas, but not a fix once spalling has begun.

2. Corrosion-Inhibiting Impregnations

How they work: These are chemicals that supposedly “neutralize” corrosion by passivating the rebar. They’re applied on the surface and soak into the pores.

Benefits:

- Sometimes delay corrosion progression.

- Can be cost-effective in small-scale maintenance projects.

Limitations:

- Performance varies widely depending on product.

- Rarely backed up with long-term independent studies.

- Ineffective when steel is already heavily corroded.

When to use: Only as part of a comprehensive program, not as a standalone “cure.”

3. Epoxy Injections

How they work: Epoxy is injected into cracks under pressure. It bonds cracked concrete back together and fills the voids with a strong glue-like material.

Benefits:

- Excellent for structural cracks where integrity is at risk.

- Bonds concrete tightly, restoring load capacity.

Limitations:

- If steel corrosion is ongoing, epoxy just seals in the problem. The steel will keep rusting, now hidden inside.

- Useless for widespread spalling.

When to use: Ideal for structural cracks without corrosion, like those caused by overload or shrinkage. Not for rust-induced spalling.

Why These Aren’t Long-Term Fixes

Once the concrete breaks and rebar corrodes, surface chemicals or injections are just “band-aids.” They can’t reverse the expansion of rust or restore lost cross-section in steel.

In fact, sometimes they make the problem worse. By sealing cracks without addressing the root cause, the rust continues in secret—until it bursts out in a bigger, more expensive failure.

As engineers, our guidance comes from standards like the International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI) guidelines and ACI 562, which lay out when to chip, clean, and patch. It’s not glamorous, but it works.

The Reality of Real Repairs

Proper concrete repair involves:

- Demolition crews carefully chipping away spalled areas (no sledgehammering randomly).

- Cleaning rebar to near-white metal condition.

- Special inspections (yes, another layer of oversight) to make sure every step is done right.

- Bonding agents and repair mortars that match or exceed the surrounding concrete strength.

Every step comes with liability—engineers, inspectors, and contractors all sign their names on this. Why? Because if something goes wrong, the safety of hundreds of people may be at risk.

Cathodic Protection: The “Middle Way”

There is one alternative that doesn’t involve chipping every inch of concrete: cathodic protection.

How it works (in plain English): Rust happens when steel loses electrons. Cathodic protection gives those electrons back using a “sacrificial anode”—usually a piece of zinc. The zinc corrodes instead of the steel, like taking a bullet for the team.

Analogy: Think of it like hooking jumper cables from your corroding rebar to a piece of cheap metal that’s willing to sacrifice itself.

Pros:

- Extends life of concrete without massive demolition.

- Proven technology in marine and bridge structures.

- Can be targeted to high-risk zones.

Cons:

- Expensive up front.

- Needs ongoing monitoring and maintenance.

- Doesn’t reverse existing damage—just slows or halts future corrosion.

Where I’ve used it: I’ve specified sacrificial zinc anodes on several Florida coastal garages and high-rise balconies. It works—but only when combined with proper repair of existing spalls.

True Story to Learn From

Many years ago in Hollywood, the Quadomain Towers almost made a costly mistake.

An outfit came to the condo board with a pitch: “We have a special liquid that, when applied to the concrete, seeps inside and cures the rusted steel.” It sounded wonderful—cheap, quick, no demolition mess. The board was excited.

I got involved. I asked the manufacturer for technical data, independent testing, or even one peer-reviewed paper showing long-term results. I called the company owner directly. What I got back was a glossy brochure and vague claims. The testing data didn’t back up their promises.

I told the board plainly: “If you go forward, you’ll just end up doing the real repairs later—and for much more money.”

Thankfully, they listened. The “miracle cure” would have been a very expensive band-aid.

Do I wish there was a magic dust that fixed spalling instantly? Absolutely. I’d probably be out of business, but people would be safer, and condos wouldn’t have to spend millions. Until then, the only real cure is proven engineering repair.

Different Perspectives

Over the years, I’ve come across plenty of people—sometimes board members, sometimes contractors, and even a few well-meaning residents—who truly believe that concrete can be “cured” with a liquid, a spray, or some sort of miracle coating. To them, the idea of taking a jackhammer to perfectly good-looking concrete seems like overkill. Why spend thousands—or even millions—when a gallon of chemical solution promises to seep into the concrete and “heal” the rebar from within?

I understand where that thinking comes from. On the surface, it feels intuitive. We live in a world where technology advances every day, and new products claim to solve problems faster, cheaper, and with less hassle. If there’s a medicine that cures disease, why shouldn’t there be a chemical that cures concrete cancer?

But here’s the problem: concrete doesn’t work like human tissue. Once steel reinforcement inside concrete begins to corrode, it expands, creating pressure that cracks and weakens the surrounding concrete. At that point, no magic liquid is going to reverse the rust or glue the broken bond back together. Some treatments, like hydrophobic sealers or corrosion inhibitors, do serve a purpose—but only as a preventive measure on concrete that’s still intact. Once the damage is visible, those products are essentially trying to bandage a broken bone with a piece of tape.

I’ve seen situations where people pushed hard for these “quick fixes” because they were cheaper, easier, or less disruptive than real repair work. But in every case, the damage kept spreading. And eventually, the repair bill was larger, the liability was higher, and the frustration was worse. It’s not that these alternative perspectives are born out of ignorance; they’re born out of hope. Hope that there’s an easier way. Unfortunately, engineering doesn’t bend to wishful thinking—it bends to physics, chemistry, and time.

| Repair Method,How It Works,Pros,Cons | ||||

| Hydrophobic Treatments,Repels water by making the concrete surface less absorbent,Reduces moisture penetration | Easy to apply | Can prolong service life if used early,Does not stop existing corrosion | Limited effect once spalling has started | Requires reapplication over time |

| Corrosion-Inhibiting Impregnations,Chemicals penetrate into concrete to slow steel corrosion,Can slow down rusting | Useful for preventive maintenance | Non-invasive application,Not effective if corrosion is advanced | Limited penetration in dense concrete | Expensive for limited benefit |

| Epoxy Injections,Injecting epoxy into cracks to seal and restore strength,Restores structural continuity | Seals cracks against water | Quick application,Does not address rusted steel | Can trap moisture and accelerate corrosion if not done properly | Best only for hairline cracks |

| Magic Chemical Products,Liquids or treatments claiming to ‘stop rust instantly’,Easy marketing appeal | Seems like a quick fix | Lower upfront cost,Unproven in long-term performance | Risk of failure | May cost more later if true repairs are needed |

| Traditional Chipping + Steel Cleaning + Patch,”Remove damaged concrete, clean/reinforce steel, patch with new concrete”,”Industry standard | Long-lasting | Backed by codes (ICRI, ACI)”,Expensive | Labor-intensive | Requires multiple inspections |

| Cathodic Protection (Sacrificial Zinc Anodes),Attaches zinc nodes that corrode instead of steel (sacrificial protection),Excellent for halting steel corrosion | Proven technology | Can extend life of repairs,Installation can be costly | Requires design and monitoring | Does not repair existing spalls |

Bibliography

Source: American Concrete Institute. ACI 562-19 Code Requirements for Assessment, Repair, and Rehabilitation of Existing Concrete Structures.

Source: International Concrete Repair Institute (ICRI). Guideline No. 03730: Guide for Surface Preparation for the Repair of Deteriorated Concrete Resulting from Reinforcing Steel Corrosion.

Source: National Association of Corrosion Engineers (NACE). Cathodic Protection of Reinforced Concrete Structures.

Source: Federal Highway Administration. TechBrief: Cathodic Protection for Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks. fhwa.dot.gov

Source: Concrete Society Technical Report No. 60. Electrochemical Tests for Reinforcement Corrosion in Concrete.

ICRI Technical Guidelines No. 03730

For additional information you can access the following:

- American Concrete Institute — www.concrete.org

- International Concrete Repair Institute — www.icri.org

- Florida Building Code — www.floridabuilding.org